This Friday we have the honor of interviewing author, architect, and critic John Hill from what is perhaps the world's most popular architectural blog site

A Daily Dose of Architecture which is nearing the 4.5 million mark on views. He also runs

A Weekly Dose of Architecture and wiki-style architectural catalogue

The Archi-Tourist. John comes to us from New York City, and some how in addition to all that, he is also currently curating a selection of lectures in and around New York City, along with select competitions and news articles.

BRANDON: John, thank you for joining us. Aside from being the most successful architectural blogger on the web, I see you are actually an Architect as well. Could you tell us a bit about your credentials? Where did you graduate from, are you RA and AIA, any other professional memberships?JOHN: You're welcome, Brandon. It's my pleasure. I graduated from

Kansas State University with a Bachelor of Architecture in 1996. From the following year until 2006 I worked for a large firm in

Chicago, gaining Illinois licensure in that time. In '06 I moved to

New York City to attend the Urban Design program at

City College, graduating with a Masters in Urban Planning the following year. I worked in a small office after graduation until the end of last year. I'm not AIA at the moment, but was in the past when the pricey tab was picked up by my employer.

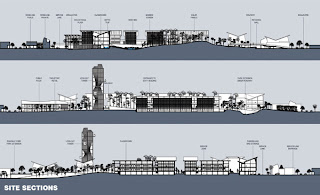

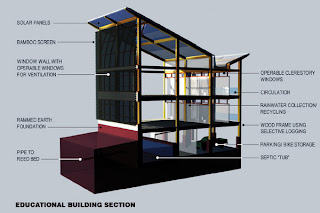

Lago Agrio project by John Hill

Lago Agrio project by John Hill

B: Urban Planning sounds pretty interesting. What exactly does it entail?J: The City College program is for people with a professional degree, like a B.Arch, so it's not geared towards planning careers, per se. Many people from CCNY continue in architecture and landscape firms, incorporating urban design into their portfolios. The program is two semesters long with

a design studio and three theory-based classes, be it history, anthropology, landscape ecology. It's more about

learning how to think about the city, particularly in a well-rounded way that balances the natural and the manmade, than learning the tools for becoming a planner. There is no such thing as a Masters in Urban Design, so it's called a Masters in Urban Planning.

Lago Agrio project by John Hill

Lago Agrio project by John HillJ: AIA membership increases each year, so the first year is pretty cheap and it close to doubles the next year, going up a smaller percentage each year after that until it levels at some point. My dues last year were approximately $700, paying for the national, state and local chapter. I was able to stay a member while in grad school, since the cost was waived. If I had my own firm I'd probably pay for it, since it would be a write-off and it might help bring in work, though I don't know how much the latter is the case in New York City.

Lago Agrio project by John Hill

Lago Agrio project by John HillJ: No, I do not have my own office. At the moment I'm between jobs, as they say. Venturing out on my own is a possibility, but I haven't taken that plunge yet. I'm using this "free time" to do some freelance writing and undertake some projects that are an extension of what I do on my web pages. That's keeping me busy at the moment, while the economy straightens itself out.

Lago Agrio project by John Hill

Lago Agrio project by John HillJ: I started

a weekly dose of architecture in 1999, when I was working at a place that did not look outside the firm's portfolio for precedents. That was something I enjoyed doing from undergrad; I'd head up to the library and flip through magazines and scan the stacks. What started as weekly sketches (a building, usually from a photo, accompanied by a description of what I could learn from it) ca. 1998 turned into the weekly web page when I realized that sharing what I was doing made sense. The name illustrated my wish to summarize things concisely and regularly.

A daily dose of architecture followed five years later, when blogs were rising in popularity and a few friends of mine were starting their own. I planned on it being less formal than the projects and book reviews featured on my weekly page, with more critique and some lightweight fare thrown into the mix. My inspiration is my continued interest in looking at the work of architects, though instead of just magazines and book, web pages are the primary sources for this information today. Many blogs do it better than I do, but I try to bring a different perspective to things and to present projects and other things not "memed" on other sites.

Lago Agrio project by John Hill

Lago Agrio project by John HillJ: Advertising revenue pays for the server I use for my weekly page, to keep that one ad-free. (I started it on a site called

Internet Trash, because it was the only free host at the time without banner ads. I realized this meant the server was sloooooooooow.) The ads not pay for much beyond maintaining the pages. I have many contacts from my years of posting on the web, be it architects, publishers, media outlets, PR folk, and other people doing what I do. Clients have been limited mainly to writing gigs, which I thoroughly enjoy. Once in Chicago somebody who liked my site paid me to meet him at a coffee shop and critique the design an architect made for his house. That was quite unique.

Lago Agrio project by John Hill

Lago Agrio project by John HillJ: Being critical might be the best skill for success. An architect needs to be able to look at things, their work included, with a critical eye, in order to guide a project in the right direction. And given that an architect will eventually have people working below them, they need to be able to give those people a certain amount of freedom and then critically assess what they've done. Architects don't need to be micro-managing, hovering above their employees to make sure they're doing something a certain way. And with a certain amount of success comes the time constraints born of it: dealing with clients, trying to get clients, presenting projects, giving lectures, riding airplanes. Having good employees and knowing how to deal with them towards the best result is important.

Lago Agrio project by John Hill

Lago Agrio project by John HillJ: I've had that happen with book reviews a few times, but since the buildings I tend to feature are ones that I like and want to share with other people, I'm usually not giving less than favorable reviews. That said I still occasionally rip on something I don't agree with and then have to defend my position in comments on the blog, but it rarely goes beyond that.

B: Given free reign on a project, what style of architecture would you most like to work with?J: I subscribe to the idea that no single style should predominate when it comes to architecture. Given free reign, what would arise would be dependent on the numerous conditions of the project (site, program, budget, client, etc.). Likewise, my favorite architects do not have a signature style. Previously I would have said

Renzo Piano is this idea's ideal, but lately he's been stuck in a formal rut of sorts, even though standouts like California Academy of Sciences remind people about his diversity.

Peter Zumthor is another name that comes to mind. Try to find a stylistic thread in his work; it's close to impossible.

B: What sort architectural and design "features" by others tend to annoy you?J: I'm annoyed by second-rate design features that appear well after their prime. One that comes to mind are those oversized, multi-story portals for frames that popped up on what seemed like every other building a few years ago, in many cases for no reason. A recent SOM building at Harvard (

http://www.som.com/content.cfm/harvard_university_northwest_science_building) has a couple of them, "living rooms" above building entries. This is not a badly-designed example, with terraces for lounging, but it nevertheless reiterates my annoyance in this feature proliferating.

B: Good, Fast, Cheap. Pick Two.J: Good and Cheap. Fast is a quality helpful to developers and other clients, not architecture.

B: What's your dream project? The one that you lay awake at night and envision one day having a benefactor to pay for it.J: Dream projects come to me when I see a site, a particularly distinctive vacant lot somewhere, for example, and then think about what would be ideal on that (usually small) patch of land. One that comes to mind is a site next to

Giddings Plaza in Chicago's Lincoln Square neighborhood, where I lived for most of my ten years between undergrad and grad school. The standard lot (approx. 25x100') was a parking lot for a big-and-tall store next door. So basically a parking lot fronted the plaza, instead of a building like the opposite side. I thought it would be possible to preserve the parking spaces for the big and tall folks buying suits next door by raising an apartment building on pilotis. The spaces would be next to the plaza and would double as market stalls when the store was closed. In the early morning it could be a farmers market; late at night beer and other late-night stuff could be sold that would enliven the plaza. Since living in New York I've learned a typical and very boring condo building has been built on the parking lot. (

http://www.fountainview-lincolnsquare.com/) Yea, it's got a green roof, but just about every other new project in the city has one.

B: What's the hardest compromise you've ever had to make on a project?

B: What's the hardest compromise you've ever had to make on a project?J: This example might not be the hardest, but it's the most memorable. For a condo high-rise in Chicago we sculpted the silhouette of the top in a manner that one area became an ideal shared rooftop terrace, with views of Lake Michigan for all residents, not just the penthouse units. This space was eventually filled in with a couple more units to maximize the profit for the developer. I fought (or at least complained) to keep it a commons area, but alas the developer won and that is how it was built. Even on a project like this one, I think that what is believed to be its most valuable component (rooftop view) should be shared by all who own part of the building, not just those who can afford it. The hard part is convincing a for-profit client to go along with that thinking and make less money in the short term. Perhaps the selling price of other units increases due to this shared amenity, making a wash of the loss?

B: Are there any vital tools and/or skills you can think of that they don't mention in school that are monumental in terms of time and/or money saved?J: Saving time is not a product of technology, even though it's lauded as such. With every advance comes new problems that take up the time saved in the benefits of CAD, or BIM, or whatever will supplant BIM. Saving time is about knowing what is NOT necessary, what does NOT need to be drawn, detailed, written, etc. This is learned, but keeping this in mind helps when faced with a deadline. Realizing later that the detail one put into one area of a presentation drawing is not visible when printed, for example, really wakes one up to what's important. Focused on the technology at hand, in this case, can lead one to missing the point. Likewise, saving money is being critical of technology and figuring out what can be taken out of a project, such as oversized mechanical systems. I have a dream where one day we will live in a world without mechanical engineers. This might sound harsh and unrealistic, but why can't we achieve the heating/cooling/ventilation with architectural means? It's been done for thousands of years. But now that we have this phenomenal technology we're in a specialization rut that makes all these extra roles needed, even though they shouldn't be. I don't think saving money is about spec'ing cheap products; it's about having an overall picture of the project and knowing what can be eliminated or reduced at all levels. And remember what looks minimal takes a lot of effort and therefore $$.

B: What did you do with all your old architectural models from school? Did you keep them as reminders, or did you recycle them with each project? Or something else?

B: What did you do with all your old architectural models from school? Did you keep them as reminders, or did you recycle them with each project? Or something else?J: They're all gone, even the ones from my recent urban design studio. (I made a full-scale mock-up of a bamboo screen facade, and now I wish I kept it.) I donated one model in undergrad to the bookstore I worked at. They hung it from the ceiling as a way to mark the architecture section. I've never recycled the materials, though if I were in school now I might be doing that. Having taken plenty of photos of my models, I've never clung to the models themselves. This might also stem from my less than stellar craftsmanship. I love a well-crafted model, but I don't have the patience to build one.

B: Have you ever met or worked with any Starchitects, or other related celebrities, such as architectural photographer Julius Schulman?J: Nope, not even close to doing that. I'd guess it's not as fun as it sounds, though working with somebody like Schulman would probably be more sane than a starchitect.

B: Do you have any parting words of advice for students pursuing a career in this field?J: My only advice would be to make sure you really love architecture and its production before getting yourself into a lifetime of being paid below your worth, working long hours, and being particularly susceptible to economic lows. I would add that you should enjoy school while you're in it, as you won't have the same freedoms after graduation. And while later you might complain that school did not prepare you for the practicalities of working in a practice, that's what working in a practice is for, learning everything outside of design, theory, etc. School is a great chance to explore and experiment; take advantage of it.

B: How long are the hours, and how low is the pay compared to the cost of living?

B: How long are the hours, and how low is the pay compared to the cost of living?J: In my experience the hours have always varied with deadlines, so for a few weeks I might have been putting in 12-hour days seven days a week, but then go back to 8-hour days five days a week for a month or so after. My last job had the benefit of very little overtime, helpful for a new father. When I was younger I could deal with getting home after midnight and being back at work first thing the next morning, day after day, but not anymore.

While the comparison of salary to house prices is not as valid in New York City (rentals are still very popular), if I take the same example, a 3-4BR in Park Slope,

Brooklyn costs about $1.5 million, though in many cases much more. A licensed architect with 10 years can expect at least an $80,000 salary. That equates to about 5% of a house per year. I don't think I'm far off with that salary, though this does show how expensive NYC can be and why people rent here. It also shows why both heads of household need to work, and why if one is an architect the other needs to be a lawyer or some other high-paid white collar to be able to afford owning in the better 'hoods.

My contention that architects are underpaid is relative to professions like engineers that have much higher salaries. Part of this discrepancy is that an engineer's contribution is more quantifiable, for lack of a better term, while an architect's contribution is more vague, even though they both contribute to the end building, and they both have insurance and liability. The lack of understanding of what architects do and are capable of leads clients to pursue other avenues, making architects low-ball their fees and bringing with it lower salaries in the meantime. Not only do architects compete with each other for jobs, they compete with engineers, contractors and developers, anybody who can stamp drawings and obtain building permits.

B: Thank you again, John, I look forward to reading your next Dose.John Hill's sites may be reached at the following URLs and are well worth the read:

http://archidose.blogspot.com (A Daily Dose of Architecture)http://www.archidose.org (A Weekly Dose of Architecture)http://architourist.pbworks.com (The Archi-Tourist)

In the spirit of building community and commerce, Southlake has returned to the idea of building a very highly social town square around their new City Hall. It's 130 acres of mixed-use development, consisting of low-density commercial, plazas, parks, and skirted by medium-density residences (like town homes and luxury apartments). With most modern cities, the center of town is the most old, polluted, decrepit part. Southlake's goal is to turn this idea on its head, and make the center of town the most attractive area by sacrificing density for aesthetics. This Town Center effect makes it as much of a place to hang out and socialize with friends as it is to shop.

In the spirit of building community and commerce, Southlake has returned to the idea of building a very highly social town square around their new City Hall. It's 130 acres of mixed-use development, consisting of low-density commercial, plazas, parks, and skirted by medium-density residences (like town homes and luxury apartments). With most modern cities, the center of town is the most old, polluted, decrepit part. Southlake's goal is to turn this idea on its head, and make the center of town the most attractive area by sacrificing density for aesthetics. This Town Center effect makes it as much of a place to hang out and socialize with friends as it is to shop. The event gazebo provides a covered stage for performers on special events, like the Fourth of July. The fountain makes a great center to the area, and becomes prime real-estate for seating when attending crowded events on hot summer days.

The event gazebo provides a covered stage for performers on special events, like the Fourth of July. The fountain makes a great center to the area, and becomes prime real-estate for seating when attending crowded events on hot summer days. The residences that skirt the town center are just a couple of blocks away. The furthest building back that you see in this photo is one of the luxury apartment buildings, with a serene, tree-lined walk right down the hill to one's choice of cafes. Though the area itself is very high-traffic, it is almost unnoticably so. Parking spaces are quite ample along the side of the street, and the only "lots" that exist are in hidden lots bordered by the backs of buildings, hiding the site of them from view. Because the town center is designed to be walked along and explored, one need not park directly in front of or beside their destination. The encouragement is to socialize with others, check out new stores, cafes, and enjoy the atmosphere.

The residences that skirt the town center are just a couple of blocks away. The furthest building back that you see in this photo is one of the luxury apartment buildings, with a serene, tree-lined walk right down the hill to one's choice of cafes. Though the area itself is very high-traffic, it is almost unnoticably so. Parking spaces are quite ample along the side of the street, and the only "lots" that exist are in hidden lots bordered by the backs of buildings, hiding the site of them from view. Because the town center is designed to be walked along and explored, one need not park directly in front of or beside their destination. The encouragement is to socialize with others, check out new stores, cafes, and enjoy the atmosphere. As previously mentioned, it gets HOT outside. Often well in excess of 100F, and temperatures over 110 are not uncommon in our hottest months. Evaporative cooling systems outside some of the stores provide inexpensive and refreshing respite from the heat, as well as moisture for the plant life in the area. Locally they are known as "Swamp Coolers", even though "Desert Coolers" would probably be a lot more apropos. But if you're ever wandering Texas and someone mentions a Swamp Cooler, this is what they're talking about.

As previously mentioned, it gets HOT outside. Often well in excess of 100F, and temperatures over 110 are not uncommon in our hottest months. Evaporative cooling systems outside some of the stores provide inexpensive and refreshing respite from the heat, as well as moisture for the plant life in the area. Locally they are known as "Swamp Coolers", even though "Desert Coolers" would probably be a lot more apropos. But if you're ever wandering Texas and someone mentions a Swamp Cooler, this is what they're talking about.

For the most part, the buildings try to stay vaguely thematic on each avenue. I say "vaguely," because as you can see there was a bit of disagreement over what type of columns or arches would be used for the colonnades in front of these shops. It is an interesting effect, however. The combination of all these different styles are united exactly by how they differ from one another. There is a feeling of both the modern and old world thrown together in a way that just seems to work. It's like "business casual" for buildings, providing enough of an air of sophistication that a nice date in formal attire could be spent wandering the restaurants and colonnades, but casual and different enough for people in a t-shirt and shorts to be comfortable shopping there as well.

For the most part, the buildings try to stay vaguely thematic on each avenue. I say "vaguely," because as you can see there was a bit of disagreement over what type of columns or arches would be used for the colonnades in front of these shops. It is an interesting effect, however. The combination of all these different styles are united exactly by how they differ from one another. There is a feeling of both the modern and old world thrown together in a way that just seems to work. It's like "business casual" for buildings, providing enough of an air of sophistication that a nice date in formal attire could be spent wandering the restaurants and colonnades, but casual and different enough for people in a t-shirt and shorts to be comfortable shopping there as well. Of course there are a few spaces where this breaks down a bit, but even at it's worst, the gaudy or out of place is often screened by the lush trees, and even when the uglier buildings are directly in front of you, the eye is immediately drawn to the more upscale buildings to the side of it.

Of course there are a few spaces where this breaks down a bit, but even at it's worst, the gaudy or out of place is often screened by the lush trees, and even when the uglier buildings are directly in front of you, the eye is immediately drawn to the more upscale buildings to the side of it. One of the more unique features is the design of the street signs. They are clearly posted, clearly visible, with good contrast for reading the lettering at a distance, a lamp directly overhead to illuminate them at night, and a visually appealing aesthetic. They harken back to an age where signs were designed to be seen by people walking by at a slow pace, rather than driving through at high speed. Despite this, they remain clearly visible from inside the car. Poorly designed, maintained, and placed street signs are one of my biggest pet peeves when I encounter them, and it is rare when one actually impresses me as these do.

One of the more unique features is the design of the street signs. They are clearly posted, clearly visible, with good contrast for reading the lettering at a distance, a lamp directly overhead to illuminate them at night, and a visually appealing aesthetic. They harken back to an age where signs were designed to be seen by people walking by at a slow pace, rather than driving through at high speed. Despite this, they remain clearly visible from inside the car. Poorly designed, maintained, and placed street signs are one of my biggest pet peeves when I encounter them, and it is rare when one actually impresses me as these do.

I feel like I saved the best for last in these photo. This plaza is one of the best-designed that I've seen in the DFW area, hands-down. Four free-standing porticos each use a trellis with lush, fragrant growth for shade. The placement of the columns, benches, the fountains, and the walks bordering it provide an excellent separation of space. Each encourages relaxation and idle conversation. Either end of the plaza is capped by a fine restaurant with patio seating, and the long edges are bordered by a walkway, then parking, the street, and then the stores. In this way, the stores themselves are available, but this plaza provides a refuge against the foot-traffic.

I feel like I saved the best for last in these photo. This plaza is one of the best-designed that I've seen in the DFW area, hands-down. Four free-standing porticos each use a trellis with lush, fragrant growth for shade. The placement of the columns, benches, the fountains, and the walks bordering it provide an excellent separation of space. Each encourages relaxation and idle conversation. Either end of the plaza is capped by a fine restaurant with patio seating, and the long edges are bordered by a walkway, then parking, the street, and then the stores. In this way, the stores themselves are available, but this plaza provides a refuge against the foot-traffic.